Life is unpredictable: The improbable is likely much closer than we think, whether that’s a sudden financial collapse, natural disaster or disease outbreak.

Together, these occurrences have a name, Black Swan events, and they can matter a lot to investing and how markets behave, beyond the impact on daily life.

Black Swan events are by definition unpredictable, yet there are some ways in which investors can attempt to capture their potential to drive performance or hedge a portfolio risk. Let’s take a closer look at the definition of these events, examples and what Black Swan investment management is.

What is Black Swan theory?

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, an essayist and former Wall Street trader and professor, introduced the larger world to the concept of Black Swan theory in his 2007 book “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable.”

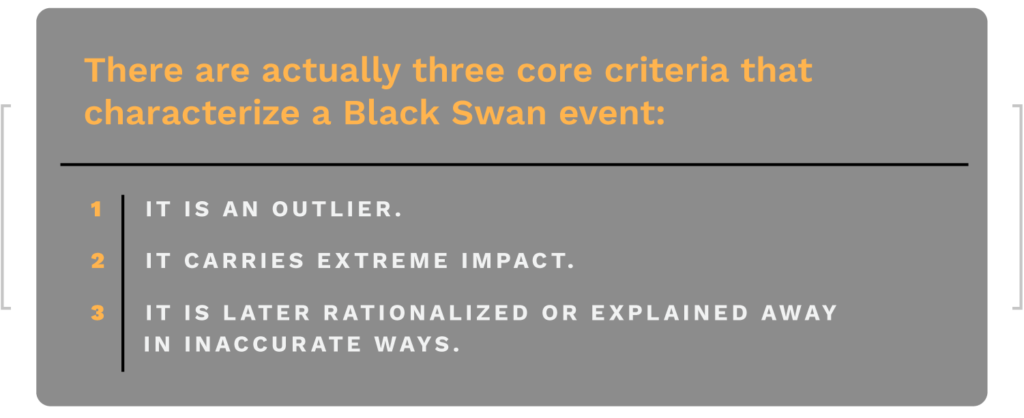

Though he had written on the subject before, Taleb set out in the book to explore his Black Swan theory. The theory holds that rare, unpredictable events that have outsize impacts are often incorrectly rationalized by humans just looking for answers, ultimately to their future detriment (i.e., you can’t grow and learn from what you can’t understand).

The central thrust of Taleb’s theory is that despite the outsized impact of these events, society takes few lessons from them. This has obvious implications not just for financial markets and investment management, but also governance and society at-large.

“The central idea of this book concerns our blindness with respect to randomness, particularly the large deviations,” Taleb wrote in an excerpt published in The New York Times. “Why do we … tend to see the pennies instead of the dollars? Why do we keep focusing on the minutiae, not the possible significant large events, in spite of the obvious evidence of their huge influence?

Why is it called a Black Swan event?

The origins of the term “Black Swan event” relate back to when the black swan (Cygnus atratus) was first discovered by Westerners, according to Taleb. To them, the only swan that could possibly exist was the white swan, as nothing in their lived experiences of knowledge of the world indicated the possibility of a black swan.

At least, until Australia was discovered, and so with it the first black swan. Taleb, in the NYT excerpt, takes this anecdote and uses it as the base for his theory. According to him, the discovery of the black swan “[i]llustrates a severe limitation to our learning from observations or experience and the fragility of our knowledge. One single observation can invalidate a general statement derived from millennia of confirmatory sightings of millions of white swan.”

By comparison, a white swan would be an event that is predictable given the tools and knowledge we have — and as we’ll see, the line between black and white swan is often blurred.

Examples of Black Swan events

As Taleb argues, Black Swan events are on the rise, and have been so since the Industrial Revolution. Some of the most notable recent Black Swan events he cites are the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and the December 2004 Pacific tsunami.

Many Black Swan events are related to financial markets or feel the impacts of other events. One good example is the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

In the run-up to the crisis, Thailand had experienced sustained speculative trading pressure against its currency. Ultimately, Thailand decided to un-peg its baht from the American dollar, which in practice meant intentionally devaluing its currency. The decision led to a domino effect across the Asia-Pacific region, resulting in stock market declines, recessions and political crises.

As the Federal Reserve’s history of the crisis shows, the crisis fits closely with Black Swan criteria: “The events that came to be known as the Asian Financial Crisis generally caught market participants and policymakers by surprise. While some vulnerabilities were well recognized before the crisis erupted, especially in Thailand, these countries’ economies were also viewed as having many strengths … However, as the crisis unfolded, it became clear that the strong growth record of these economies had masked important vulnerabilities.”

Whereas the baht’s unpegging may have garnered attention and blame, it was likely “years of rapid domestic credit growth and inadequate supervisory oversight” that really fed the financial crisis.

In this way, the 2007-08 global financial crisis can be seen as another likely Black Swan event. There wasn’t much overt prelude to the crisis, but the impact was swift and devastating. In September 2008, Lehman Brothers went under, and by the end of October the S&P 500 had shed nearly 20% in its worst month on record, at that time.

Other recent Black Swan events commonly cited include the:

- Dot-com market crash of the early 2000s.

- Brexit vote and aftermath.

- Black Monday for the American stock market in 1987.

- Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Are US presidential elections considered Black Swan events?

An important note is that some elections can also be considered Black Swan events, particularly from an investor’s perspective. Unlikely victories, shock upsets and total stunners can also create shockwaves for markets that can resemble the impacts of a Black Swan event. For example, the Chicago Daily Tribune was so confident in the outcome of the 1948 presidential election that it printed the infamous “Dewey Defeats Truman” headline before results were final, leading to confusion and market shifting.

While presidential elections can create effects that mimic black swan events, the election process is usually a more predicted stressor to the market than the events described above. However, it is possible for an election outcome to create a black swan event in the market should other stressors come alongside that news.

Was the COVID-19 pandemic a Black Swan event?

Importantly, the housing crisis that drove the 2008 collapse did not go entirely unnoticed. Many hedge funds and other market watchers saw the signs. What may have been an outlier to some doesn’t carry the same unpredictability to others.

If you ask Taleb, the originator of Black Swan theory, the COVID-19 pandemic was decidedly not a Black Swan event.

Yet, here again the issue of perspective is critical. While the fact a pandemic occurred may not have been surprising to some infectious disease experts and others, it certainly caught markets and the global population off guard, leading to substantial economic and societal damage. The COVID-19 pandemic may very well have been a Black Swan event, but like with the other financial crises mentioned, the lessons learned from it are going to be crucial to improving readiness and mitigating risk.

What is Black Swan investment management?

Black Swan investment management is in effect a strategy that often eschews traditional forecasts, as Black Swan events can’t be predicted, and instead looks to capitalize on uncertainty in other ways.

Often, Black Swan investment management takes the form of a hedge fund that pursues a tail-risk strategy, a strategy endorsed by Taleb himself. Tail risk, according to according to Chief Investment Officer Magazine, is “the probability that an event on the narrow end of a bell curve of outcomes has a greater chance of coming true that standard-thinking investors feel comfortable with.” The magazine offered an example in that a tail-risk hedge would aim to protect long positions on the S&P 500 with derivatives (e.g. options and futures contracts) that track the CBOE Volatility Index, or VIX.

Of course, Black Swan investment management carries with it inherent risks. Unpredictable and chaotic events can be, well, unpredictable and chaotic. The key thing to remember in Black Swan investment management is that even if it pays off once, investors can’t suddenly think they can predict the unpredictable, as The Wall Street Journal notes.

Learn more about how Magma strategizes volatility

Market volatility can be a common after-effect of a Black Swan event, and it’s also at the center of Magma Capital Funds’ investment strategy. We actively allocate the investments of our flagship Magma Total Return Fund in response to volatility signals and seek to find the most opportune assets during any given market. Sometimes it is most advantageous to short equities like the S&P 500 or the Nasdaq-100, and other times the fund will take long positions. To that end, the Total Return Fund is designed to perform well in both calm markets and Black Swan environments, among other market conditions.

Want to learn more about the specifics of the Total Return Fund and how to invest? Contact us today.